Bright Dart Read online

Page 2

If Wollweber was offended he took great care not to show it. He had it on good authority that Kastner was highly thought of by Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler and by General of the SS Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the Reich Security main office, and in his view, it was politic not to antagonise a man who had such influential and powerful friends. Wollweber eased his bulky figure into the car, closed the door and started the engine. Looking over his shoulder, he reversed out of the parking space.

Kastner said, ‘I assume the body has already been disinterred and examined?’

‘We took action immediately we received your instructions over the teleprinter link.’

‘And?’

‘We are unable to ascertain the identity of the air-raid victim but it certainly isn’t Major-General Gerhardt.’

‘You’re quite sure of that?’

‘We examined the body most carefully and there was no sign of an old tattoo scar. Do you wish to see for yourself, Herr Kastner?’

‘No,’ said Kastner, ‘we’ll drive straight to Iserlohn. I want to have a talk with the so-called widow. She has some explaining to do.’

The car bumped over the potholes in the cobbled road and then swerved wildly as the offside front wheel momentarily slid into the tramline. The Hauptbahnstrasse no longer existed; it was merely a highway cutting through acres of rubble, but here and there a fire-blackened shell of an apartment building remained and on the walls the fading chalk marks told their own story—Number 48, ten dead in the cellar, Number 126, eight dead in the cellar, query one still alive? Sometimes it was simpler to pour in quicklime than to dig out the bodies, and in the industrial cities it was not unusual to see an array of postcards displayed outside the newsagents from relatives seeking news of another’s survival.

The scene depressed him, and Kastner, suddenly feeling in need of a cigarette, took out a packet of Lucky Strike and lit one.

He had developed a liking for American cigarettes and, although he had an almost unlimited supply provided by a friend in the Luftwaffe who confiscated them from prisoners of war under interrogation, he saw no good reason why he should offer one to Wollweber.

13

Wollweber said, ‘The whole of the Ruhr has had a bad time of it.’

‘It isn’t any picnic in Berlin either but we learn to live with it.’

‘We all do,’ Wollweber said hastily, ‘because in the end we know that victory will finally be ours.’

He glanced surreptitiously at Kastner to see if there was any reaction, but the face of the man sitting next to him was devoid of expression. Wollweber was more than a little afraid of him and with good reason.

Kastner was not human; it was said that he rarely needed more than four hours sleep in twenty-four and that when others dropped in their tracks from sheer exhaustion, he was still fresh and alert. He was acknowledged to be the best interrogator in the Reichs-Sicherheits-Hauptamt and this was partially attributable to the experience he had gained in the Criminal Police from 1931 until he transferred to the SD in 1937. He was an ardent Party member, who owed much of his early advancement to Reinhard Heydrich, but when the latter was assassinated in Prague by Jan Kubis and Joseph Gabchick with the help of the Czech Resistance Movement, he had proved himself to be clever and able enough not to need a patron. At thirty-seven, he was the personification of the mythical blond Aryan created by Goebbels but rarely seen in the flesh. He was also a ruthless killer.

Wollweber said, ‘The pre-alert was issued just a few minutes before I left the office.’

‘Oh, yes?’

‘I expect it will be the Americans again. It beats me how they can keep on coming in daylight when the Luftwaffe is knocking them out of the sky.’

‘Are you doubting the claims made by our pilots?’

He was not sure whether Kastner was pulling his leg or not, but Wollweber wasn’t taking a chance on it. ‘Of course not,’ he said quickly.

Kastner opened the side window and flicked the cigarette out into the gutter. ‘Naturally,’ he said, ‘I assume you’ve interrogated the mortuary attendant?’

The question, coming when it did, almost caught Wollweber off guard. It hadn’t occurred to him to interrogate the attendant but he wasn’t going to admit it.

‘We’ve had one session with him but I plan to have another shortly. I believe he could tell us a great deal more about Frau Gerhardt than he has disclosed so far.’

‘Instead of gossiping with the man,’ Kastner said bitingly, ‘ask him how the identity papers belonging to a Wehrmacht General 14

came to be found on the body in the first place. And understand this, I want the answer by the time I get back to Berlin tonight.’

Wollweber licked his lips. ‘I’ll get on to it as soon as we’ve finished our business in Iserlohn,’ he said nervously.

The sirens started to wail as they reached the outskirts of Dortmund and, above the noise of the car, the faint but distinctive crack of the 88mm flak guns could be heard, and later, when they were on a parallel course, Wollweber saw the myriads of white cotton balls which marked the burst of each shell hanging limply in the sky in the far distance.

‘Looks as if Düsseldorf is getting it,’ he said anxiously. There was no reply and, taking the hint, Wollweber lapsed into silence.

No bomb had yet fallen on Iserlohn. The trams still clanked through the cobbled streets, the market was still held twice a week on the Schillerplatz and, apart from a scarcity of goods on display in the shop windows and the usual propaganda notices outside the post office, there was little tangible evidence of the war. The town had had its share of evacuees from Essen, Dortmund and Düsseldorf and there was a Flak Unit in the barracks on the outskirts, but somehow these strangers did not greatly affect the lives of the inhabitants.

Langestrasse was one of a number of streets which ran out of the market place and climbed the steep hill dominating that particular section of the town. There were a number of small shops and shabby-looking flats at the lower end of this street, but farther up, the apartment buildings gave way to detached houses of individual character. In comparison with those on the crest, Number 77 Langestrasse was a comparatively modest house for a man of Gerhardt’s standing.

Kastner said, ‘Are you sure this is the right place?’

‘I did check the address with the post office earlier this morning.’

‘That’s what I call foresight.’

‘Should I come with you?’

‘No,’ said Kastner, ‘you can wait outside.’

He left the car, walked briskly up the front path and rang the bell. The photograph they had on file in the Amt IV did not do justice to the woman who answered the door, for the camera had given her a tight-lipped expression which made her seem plain and uninteresting. She was wearing a navy-blue suit over a white silk blouse, low-heeled shoes and silk stockings, all of which Kastner thought must have been acquired in Paris at some time or other. The long brown hair softened the angular face, and in his opinion, she appeared much younger than thirty-five.

Kastner said, ‘Frau Christabel Gerhardt?’

The woman nodded.

15

Kastner held out his identity card. ‘I’m from RSHA, Berlin,’ he said. He waited to see if there would be any reaction, but although the brown eyes were watchful, she was quite calm. ‘I’m here on official business. May I come in?’

‘Please do,’ she said quietly. She stepped to one side, and as he entered the tiled hall, she closed the door behind him. Kastner followed her into the lounge and sat down in an armchair facing her across the width of the room. Silver-framed portraits of her children and of Gerhardt in army uniform were carefully arranged on top of a large writing desk, and on each window ledge there was a row of potted plants. Through the half-drawn curtains in the alcove he could just see the heavy furniture in the dining room.

‘Where are the children?’ Kastner said abruptly.

‘At school.’ She glanced at her wristwatch and then added

, ‘But they should be home shortly.’

She was much too calm for his liking and he sensed that he would have to apply a great deal of pressure before she caved in.

No doubt Christabel Gerhardt had mentally prepared herself to face the fact that eventually she would be questioned by the Gestapo and had tried to anticipate the line her interrogator would take.

Kastner said, ‘We’re trying to locate your husband, Frau Gerhardt.’

‘You must know he’s dead,’ she said quietly. ‘He was killed in an air raid.’

‘And you identified the body?’

‘Yes—it was a horrible experience. He was terribly mutilated.’

Kastner took out a packet of cigarettes. ‘Do you mind if I smoke?’

he said.

‘Not at all.’

He held out the packet towards her. ‘Would you care for one?

They’re American.’

‘I don’t, thank you.’

Kastner lit the cigarette and inhaled. ‘It must have been very harrowing for you,’ he said softly, ‘no head, no legs—imagine being confronted with such a sight.’

‘I tried not to look and there was no need to really because they had found his wallet and papers, and when they drew back the sheet and I noticed the wedding ring I’d given him on his finger, I knew it had to be Paul.’

‘And when was the last time you’d seen him alive?’

‘He came home on leave on the Wednesday and then left for Dortmund on the afternoon of Friday the 18th of August.’

‘And subsequently, on the 28th of August, his body was dug out from beneath the ruins of the Kaiserhof Hotel?’

16

‘Yes, it was a great shock.’

Kastner smiled thinly. ‘I don’t want to distress you,’ he said,

‘but I just want to clear my mind on a few points.’

‘Of course, I understand.’

‘Do you know what kind of place the Kaiserhof is?’

‘Yes,’ she said reluctantly, ‘the police informed me that it was a favourite haunt of the local prostitutes.’

‘And because he’d been with another woman, you allowed him to be buried in Dortmund?’

‘He’d left me,’ she said flatly.

‘Well, Frau Gerhardt, don’t grieve too much about it,’ Kastner said drily, ‘your husband’s still alive and well and in hiding somewhere. We matched the body against his medical documents and certain tattoo scars were missing.’

‘I don’t believe it!’ She thought she had struck the right note of incredulity but Kastner was not impressed.

‘You know, I think you’re a very good actress, Frau Gerhardt, but I’m not being taken in. Your husband had to die because he was involved in the July Bomb Plot.’

‘You know that’s completely untrue.’

‘He sent an armed detachment into Berlin on the afternoon of the 20th of July with orders to …’

‘You have the wrong man, Herr Kastner,’ she said calmly.

‘Lieutenant-Colonel Jurgens, acting entirely on his own authority, mobilised one company and set off for Berlin. As soon as my husband heard about it, he arranged for the column to be turned back at Zossen.’

‘Because he developed cold feet.’

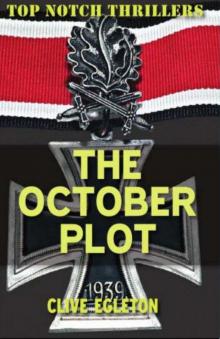

‘My husband was awarded the Knight’s Cross for bravery,’ she said angrily. ‘He certainly wouldn’t run away from a man like you.’

‘He saw Stauffenberg frequently.’

‘Naturally Stauffenberg was Fromm’s Chief of Staff so he could hardly avoid meeting him.’

Kastner rose from his chair, walked across the room and leaned over Christabel Gerhardt. Reaching past her, he stubbed out his cigarette. ‘He was involved, and you helped him to disappear, and I want to know where I can find him.’

‘He was not involved. I did not help him to disappear and I certainly don’t know where he is now. And furthermore, Herr Kastner,’ she said quietly, ‘I’m not interested in his whereabouts.

There was another woman.’

‘Whose name is?’

‘If I knew that, I’d tell you.’

She was hard, much harder than he had expected and he admired 17

her for it, but despite her outward composure, her eyes were dilated with apprehension. Given a little time to think things over, she would begin to sweat, and he could afford to wait.

‘I hope,’ he said harshly, ‘I hope for your sake that he wasn’t involved in the Bendlerstrasse conspiracy. Perhaps you recall the case of old Field-Marshal Witzleben? He was tried on the 8th of August and two hours later we hanged him at Plotzensee from a butcher’s hook on a short length of piano wire. He was naked when he died and he was hung up like a side of beef.’ He smiled icily. ‘As a matter of fact, we filmed the executions on the orders of the Führer. Did you know that?’

‘No,’ she said huskily, ‘I didn’t.’

‘Perhaps I will arrange a private viewing of the film for you—

after all, it could happen to you.’

She swallowed hard and he could see that it required all of her strength of will to stay calm. ‘Before you make any further accusations,’ she said, ‘you ought to know that two days before my husband came on leave, he had a long and private talk with Reichsführer Himmler.’

For a few brief moments he was completely thrown off his stride as he tried to weigh the implications which lay behind that assertion. Where Himmler was concerned you could never be sure.

‘Really?’ Kastner said quietly. ‘Should that impress me? After all, Reichsführer Himmler replaced Fromm as C-in-C of the Reserve Army at midnight on the 20th of July and it’s only natural that he should wish to meet his Divisional Commanders.’

‘I thought you ought to know, that’s all.’

Kastner stepped back. ‘I shall call on you again,’ he said, ‘and until then your movements will be confined to the environs of Iserlohn, and of course you will inform us immediately should your husband or any of his friends attempt to get in touch with you. Do I make myself clear?’

‘Perfectly.’

‘Goodbye for now then, Frau Gerhardt.’

His footsteps echoed in the hall, the door slammed behind him and presently she heard the car start up and drive off, but it was some minutes before her heart stopped thumping. Before he went away, Paul had warned her that something like this would happen but because they had had so little time to prepare a foolproof cover story, it had been worse than she had expected.

Kastner was toying with her like a cat with a mouse, and she knew that from now on the telephone would be tapped, her letters would be intercepted and opened before they were delivered, and she would be under constant surveillance.

18

On the afternoon of Tuesday, 22nd August, 1944, a sales representative of the Uddenholm Steel Corporation left Hamburg on the through train for Helsingör. His papers, which were in order, were checked at Puttgarten and then again before he boarded the ferry to Sweden. As soon as he landed at Hälsingborg, he caught the first train to Stockholm where he presented himself at the British Embassy claiming that he was Major-General Paul Heinrich Gerhardt, holder of the Knight’s Cross and formerly commander of the Panzer Grenadier Division Ludendorf, but now acting as an emissary of the German Underground.

On Saturday, 26th August, he was flown to England in the bomb bay of an unmarked RAF Mosquito and subsequently was taken by car from Middleton St George to Aylesbury Prison where he was held in solitary confinement for a week before being transferred to Abercorn House for interrogation in depth.

In his desire to gain the trust and eventually the cooperation of the Allied Intelligence officers who were questioning him, Gerhardt willingly disclosed details of the order of battle, state of training and general morale of the various formations in the Reserve Army, and in so doing, earned their contempt. And as a result, it began to dawn on Gerhardt that no one was interested in hearing why he had chosen to come to England, which was a pity, because he had a plan to end the war.

19

3

EVEN THOUGH THE window was barred, it did not restrict the view of the rolling English countryside which stretched before Gerhardt as far as the eye could see. Oak, elm and beech tree dotted the landscape in haphazard fashion, in keeping, it seemed, with the irregular shape and size of each field. To the professional eye it was good tank country except that the sharply undulating nature of the ground coupled with a number of false crests would restrict the field of fire of any Panther equipped with the long 75mm gun and in consequence the armour would tend to move cautiously.

But, in truth, the Panzer Divisions had lost their dash and élan long before they were up-gunned with the 75 and 88mm, and of what use were the Panthers and King Tigers if the crews were incapable of maintaining them? Nowadays mechanical failure accounted for almost half the total tank losses, but three years ago it had been a different story.

Gerhardt had been with Guderian’s Panzer Group then, spearheading Von Bock’s thrust into central Russia, and nothing had stopped them. From Brest Litovsk to Smolensk, motoring on their tracks, they’d gone through the Soviet armies like a knife through butter, but in the end the cup had been snatched from their lips. The road to Moscow lay open but instead they had found themselves back-tracking some four hundred miles to complete the destruction of Budyenny’s forces trapped in the Kiev encirclement. They’d all but worn out the tracks on their Mark IIIs and IVs but, by God, they’d achieved something no other army had or ever would.

The mirror above the washbasin reflected the mixture of pride and arrogance in his lean face and Gerhardt was suddenly disturbed, for such an attitude would not make an ally of Ashby.

Tact and honesty and perhaps diffidence were required and all he had to offer was bravery. This meeting could be the most important event in his life, and if he were successful, the effects could be far reaching.

A Bedford fifteen hundredweight came down the long narrow drive and drew up outside the house and a tall officer in battledress stepped out. Looking down from above, Gerhardt saw that he was a Lieutenant-Colonel and knew instinctively that 20

Bright Dart

Bright Dart