Bright Dart Read online

‘ Our strength lies in having a simple plan which, if boldly executed, will not fail.’

Yet in wartime, few things are simple and even the minor cogs in Operation Leopard – the attempt to kill Deputy Führer Martin Bormann – have a vital part to play.

The October Plot, conceived by a defecting German General and championed by ‘the most dormant intelligence department in the War Office’ is a bold scheme to end World War II in 1944, but could it be seen as the British making a secret peace deal behind the backs of their Allies? The Americans and the Russians are suspicious of the plan and some in London strongly opposed to it. In Berlin, however, there are some who might just want it to succeed.

On first publication, The Sunday Times called it ‘A very fine story, shrewdly researched and splendidly written’ and The Guardian classed it as a ‘Well-constructed adventure thriller…alarms and excursions galore’.

Clive Frederick William Egleton (1927–2006), the only child of a truck driver, was born in South Harrow, Middlesex and claimed that ‘from the age of six’ he wanted to be a soldier. He enlisted, underage, on D-Day 1944 and was assigned to the Royal Armoured Corps to be trained as a tank driver. He subsequently transferred to the infantry and was commissioned into the South Staffordshire Regiment, serving in India, Hong Kong, Germany, the Persian Gulf and East Africa before retiring as a Lieutenant-Colonel on the thirtieth anniversary of his enlistment. His years of experience in Intelligence and Counter-Intelligence work proved fruitful for his second career as a writer of thrillers, a career which began whilst he was still in the army. Seven Days To A Killing , his fourth novel which was filmed by Don “Dirty Harry” Siegal as The Black Windmill , was the breakthrough book which propelled him into the front rank of British thriller writing and he was to write forty more.

Top Notch Thrillers

Ostara Publishing’s Top Notch Thrillers aim to revive Great British thrillers which do not deserve to be forgotten. Each title has been carefully selected not just for its plot or sense of adventure, but for the distinctiveness and sheer quality of its writing.

Other Top Notch Thrillers from Ostara Publishing: John Blackburn The Young Man from Lima David Brierley Cold War

David Brierley Big Bear, Little Bear

Brian Callison A Flock of Ships

Victor Canning The Rainbird Pattern

Desmond Cory Undertow

Francis Clifford Time is an Ambush

Francis Clifford The Grosvenor Square Goodbye Clive Egleton Seven Days To A Killing

John Gardner The Liquidator

Adam Hall The Ninth Directive

Adam Hall The Striker Portfolio

Geoffrey Household Watcher in the Shadows Geoffrey Household Rogue Justice

Duncan Kyle A Cage of Ice

Duncan Kyle Black Camelot

Duncan Kyle Terror’s Cradle

Jessica Mann Funeral Sites

Berkely Mather The Pass Beyond Kashmir Philip Purser Night of Glass

Geoffrey Rose A Clear Road to Archangel George Sims The Terrible Door

Alan Williams Snake Water

Alan Williams The Tale of the Lazy Dog Andrew York The Eliminator

Andrew York The Deviator

Andrew York The Predator

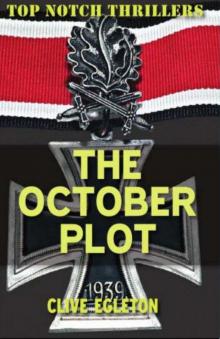

The October Plot

Clive Egleton

Ostara Publishing

This book is for David and Sheila with my true admiration First published 1974

Ostara Publishing Edition 2012

Copyright © 1974 Clive Egleton

The characters in this book are entirely imaginary and bear no relation to any living person.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which this is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 9781906288 891

A CIP reference is available from the British Library Printed and Bound in the United Kingdom

Ostara Publishing

13 King Coel Road

Colchester

CO3 9AG

www.ostarapublishing.co.uk

The Series Editor for Top Notch Thrillers is Mike Ripley, author of the award-winning ‘Angel’ comic thrillers, co-editor of the three Fresh Blood anthologies promoting new British crime writing and, for ten years, the crime fiction critic of the Daily Telegraph. He currently writes the ‘Getting Away With Murder’ column for the e-zine Shots on www.shotsmag.co.uk.

‘Of course it was a long shot but even now with the benefit of hindsight, I still think it was worth the gamble because it was the last opportunity we had to end the war in Europe that year. Although we were forced to rely heavily on Major-General Gerhardt of the Panzer Grenadier Division Ludendorf, whose contacts in the German Resistance appeared to enjoy some kind of special immunity from the Gestapo, I never completely trusted that man and to be honest, if Ashby had not been in command, I doubt very much if I would have volunteered. At first it seemed to me that either Gerhardt was just another crackpot like Hess who’d come before him, or else he was trying to save his own skin after the débâcle of the July Bomb Plot. Ashby, however, was the one person who had unswerving faith in the enterprise and the strength of purpose to see it through when it seemed that every hand was turned against us. In my view, he was just about the most under-rated man in the entire British Army, and whatever his faults, there is no escaping the fact that under his leadership we nearly brought it off and re-drew the map of Europe.’

An extract taken from a copy of the After Action Report submitted to the Office of Strategic Services which was given to the author by Major John Ottaway (Retd.) US Army, who was attached to Force 272 for Operation Leopard—the intended assassination of Martin Bormann in the Hall of Peace, Münster, Westphalia on Saturday, 14th October, 1944.

BERLIN

Thursday, 20th July, 1944

‘Caesar has his Brutus—Charles the First, his Cromwell—and George the Third (“Treason”, cried the Speaker) … may profit by their example. If this be treason, make the most if it.’

PATRICK HENRY IN A SPEECH IN THE VIRGINIA CONVENTION, 1765.

1

THE CITY SWELTERED in the July heatwave, and in the distance Jurgens thought he could hear the rumble of an approaching storm. From his vantage point on the roof of the Bendler Block he could see the massive Flak Tower in the grounds of the Berlin Zoo which, like a giant sugar cube, rose to a height of forty-five metres to dominate the skyline. There were five similar towers in the Humboldthain and Friedrichshain Districts all of which had been constructed between 1941 and 1942, but at this moment in time, they were only of passing interest.

Since twelve minutes past four that afternoon the city should have been in a state of unrest, but in the Tiergarten people were just strolling home from work, and when he looked towards Wilhelmstrasse some fifteen hundred metres to the north-east, there was no sign of any activity around the Reich Chancellery or the Foreign Office. He was crouching on the roof of the Reserve Army Headquarters, the hub and nerve centre of the revolt, and the only soldiers in evidence were the sentries on the main gate.

The army should have been pouring into the city from every direction to seal off the Government quarter, to arrest Goebbels and to seize the radio station, but instead they were quietly skulking in their barracks because no one would believe that Hitler was dead.

7

Stauffenberg had taken a bomb into the Führer Headquarters at Rastenburg, had seen it go off and when he’d said that it was impossible for anyone to survive a blast of that magnitude, his word had been good enough for Hasso Jurgens, but not, it seemed, for Maj

or-General Paul Heinrich Gerhardt. When he’d learned that Jurgens, in response to codeword ‘Operation Valkyrie’, had set off along Route 96 with a hundred and thirty men drawn from the headquarters staff of the Panzer Grenadier Division Ludendorf, he’d telephoned OKH Headquarters at Zossen and arranged for the small column to be turned back thirty-two kilometres to the south of the city.

Jurgens had come on alone because he thought he owed it to Stauffenberg, Beck, Quirnheim and the other conspirators, but for all the good he was doing, he might just as well have stayed at home. The scene in the Chief of Staff’s office had depressed him immeasurably because, at a time when action was required, there was Colonel-General Beck engaged in a futile debate with Fromm, the commander of the Reserve Army, and Fromm had been trying to persuade the old man to commit suicide because he’d heard from Keitel at Rastenburg that the Führer was still alive. They ought to have shot Fromm, but instead they’d placed him under arrest and then, as if anxious not to seem unduly harsh, they’d sent down to the mess for a cold tray and a bottle of wine so that he shouldn’t go hungry. It was, thought Jurgens, a damn funny way to run a revolution.

He glanced in the direction of Prince Albrechtstrasse where the Gestapo Headquarters was situated and wondered how much longer it would be before there was some reaction from that quarter.

Sooner or later they would wake up to the fact that something very odd was going on in the Bendlerstrasse and then there would be all hell to pay. Perhaps they already knew but were reluctant to make a move against the conspirators because they feared a head-on clash with the army. Well, Jurgens had news for them—they’d find any number of allies inside the Bendler Block who were only too keen to do their duty for Führer and Fatherland. He’d heard them talking in the corridor on the third floor on his way up to the roof and he knew damn well that they wouldn’t lift a finger to help Stauffenberg. And remembering this, Jurgens began to feel isolated and cut off and he wished he knew what was happening. He was prepared to bet that Stauffenberg was still on the telephone making one last vain effort to persuade the reluctant Generals to act, but they never would. They’d sworn an oath of personal loyalty to the Führer in August 1934 and they were afraid to go back on it. Unable to bear the suspense any longer, Jurgens suddenly left his post on the roof and went back inside the building.

8

The staff officers were still lounging about in the corridor on the third floor but now they seemed more excited, and an officious Major in the intelligence branch was attempting to organise a search of the building. As Jurgens came towards the group, he stepped forward and accosted him.

‘Did you hear the news flash on the Deutschlandsender a few minutes ago, Colonel?’ he said.

‘No, I didn’t,’ Jurgens said abruptly.

‘There was a bomb attempt on the Führer but fortunately he sustained no more than a few slight burns and bruises. I knew damn well there was something funny going on. I’ve just been talking to the Signal Corps Lieutenant in charge of the communication centre and he tells me that he’s had to deal with a flood of signals.’

‘What’s so unusual about that?’

‘They were addressed to Paris, Vienna, Athens and Brussels and the originator is supposed to be Field-Marshal Erwin von Witzleben.’

‘Yes?’

‘Well, don’t you find that odd, Colonel? Fromm commands the Reserve Army, not Witzleben.’

‘I see. Have you spoken to Colonel Stauffenberg about this?’

‘I can’t get near him.’ The Major eyed Jurgens suspiciously.

‘May I ask what you’re doing here, Colonel?’

‘I’m here on behalf of my commander. He wanted to know why the Panzer Grenadier Division Ludendorf is being starved of replacements, but I can’t find a single officer in the Personnel Branch.’ He frowned and then said coldly, ‘I fancy they’re too busy gossiping elsewhere.’

‘We have reason to believe that there is a conspiracy against the Führer …’

‘And what do you propose to do about it, Major—?’

‘Steiner, sir. I’m about to organise a search party.’

‘Oh, yes?’

‘But we’re unarmed.’

Jurgens tapped the pistol holster on his hip. ‘But I’m not,’ he said. ‘While I make a reconnaissance of the second floor, I suggest you try to obtain some arms and ammunition from the Town Commandant.’ He pushed Steiner to one side and walked on.

His heart was thumping wildly.

A small crowd had gathered in Stauffenberg’s office now and among the newcomers Jurgens recognised the figure of Witzleben.

Apart from lecturing Beck and pointing out how badly the whole affair had been mismanaged, the Field-Marshal wasn’t contributing a great deal towards the success of the enterprise.

9

It suddenly came home to Jurgens that he was watching the death throes of the conspiracy and the urge to run was irresistible.

He walked down to the main entrance, strolled past the guards and entered the forecourt. He could see the Kubelwagen parked between an Opel ‘Blitz’ and a Wanderer saloon but there was no sign of his driver, and then he remembered that he’d told the Ukrainian auxiliary to wait in the canteen, and although momentarily he toyed with the idea of going back inside to fetch him, he eventually decided against it. The need to get well clear of the Bendler Block was uppermost in his mind and he set off at a brisk pace towards the Tiergartenstrasse.

Any thought of rejoining his unit was out of the question because inevitably someone at Zossen would remember Gerhardt’s frantic telephone call and the Gestapo would run a check on him. If he was to survive, he’d have to go into hiding and, as the first step in that direction, he would have to get rid of his uniform. In all Berlin he knew only one person who might be prepared to help him. His sister, married to a doctor, had a house in Falterweg on the edge of the Grunewald Forest.

As he turned into the Potsdamer Platz, the leading elements of the Berlin Guard battalion passed him going in the opposite direction towards the Bendlerstrasse. Quickening his stride, he walked into the station and, in an attempt to cover his tracks, bought a ticket to Nicollassee which was one stop beyond his chosen destination. He took the S Bahn up to Friedrichstrasse, changed on to the Potsdam line and then left the train at Grunewald to walk the rest of the way to the house in Falterweg.

He’d almost reached it when it occurred to him that he’d overlooked one vital factor. When his father had died in the summer of ’41, Jurgens, who was a bachelor, had nominated his sister as his next of kin and her address was listed on his personal record card. In retrospect, Zossen had been the critical point because if he’d then turned back with the rest of the column, he might just have got away with it, but in choosing to go on alone, he’d tipped his hand. If he was lucky it might take the Gestapo a few hours to reach the conclusion that he’d been involved in the conspiracy, but this in no way altered the fact that sooner or later they would check out his next of kin. Although in his own mind he was absolutely certain that the most savage reprisals would be taken against anyone who even unwittingly helped him now, it still required a conscious effort of will-power to walk on past Falterweg and enter the Grunewald.

He moved deep into the forest and then turning off the ride, he found a quiet spot which would suit his purpose. As if in a trance, he loosened the flap on his pistol holster and withdrew the 9mm 10

Luger automatic. It was a weapon that his father had carried in the First World War and in presenting it to his son, he could never have foreseen the use to which it would eventually be put.

Jurgens looked at it, hesitated and then snapped the toggle action back to send the round sliding into the breech. It was a precision-made weapon and even after the passage of years, its mechanism functioned perfectly.

At ten minutes past nine on the evening of the 20th July, 1944, Hasso Jurgens opened his mouth and thrusting the barrel upwards into the roof, squeezed the trigger. Travelling on an inclined plane of fi

fty-five degrees, the bullet in exiting removed a large fragment of his skull and spattered the bushes behind him with particles of bone and brain tissue.

In choosing to die by his own hand, he had inadvertently pointed an accusing finger at Gerhardt and set in motion a train of events which, taken collectively, would have a profound effect on the final outcome of the war.

11

Friday, 15th September to Sunday, 8th October, 1944

‘All the business of war, and indeed all the business of life is to endeavour to find out what you don’t know by what you do; that’s what I called “guessing what was the other side of the hill”.’

ARTHUR WELLESLEY, DUKE OF WELLINGTON, 1769–1852

2

DORTMUND STATION was operational again but only just. As he stepped down from the train and looked up, Kastner could see the pale September sky through the twisted girders of the roof above the platform. A haze of brick dust hanging in the air produced a false overcast and blurred the definition of each object in sight. The rubble was stacked in untidy mounds in the centre of the island and, as he walked towards the exit, particles of broken glass crunched under his shoes. In passing, he noticed a derelict 4–6–

2 locomotive abandoned in a siding while some two hundred metres beyond this, the down lines were a tangle of corkscrewed rails and gaping craters.

Wollweber was waiting for him outside the station with a 1939

Mercedes limousine. He was a short, corpulent, middle-aged man who seemed to think that it was obligatory for a member of the SD to wear a black trenchcoat and dark Homburg even on a warm day such as this. His watery eyes blinked in recognition behind the gold-rimmed glasses and a tentative smile etched itself on his rounded face.

‘I hope you had a good journey, Herr Kastner?’ he said politely.

Kastner opened the door, tossed his briefcase on to the back 12

seat and got inside the car. ‘You know very well that the train was two hours behind schedule,’ he said curtly, ‘so let’s not waste time making polite conversation.’ He closed the door in Wollweber’s face and then waited impatiently for the older man to join him.

Bright Dart

Bright Dart